The tundra was still except for distant sounds of flowing water. Nothing in sight moved.

Bernard cupped his hands around his mouth. “UhghUhhhgh! Uh! Uh!”

Far down the river, something moved. Something massive.

Willows cracked and snapped. Small trees shook. A heavy body crashed through the riverbank brush straight toward us.

The 11” barrel on my AR-15 pistol swung toward the approaching sound. Let others question the wisdom of trusting a short-barreled AR-15 in this situation; I had complete confidence.

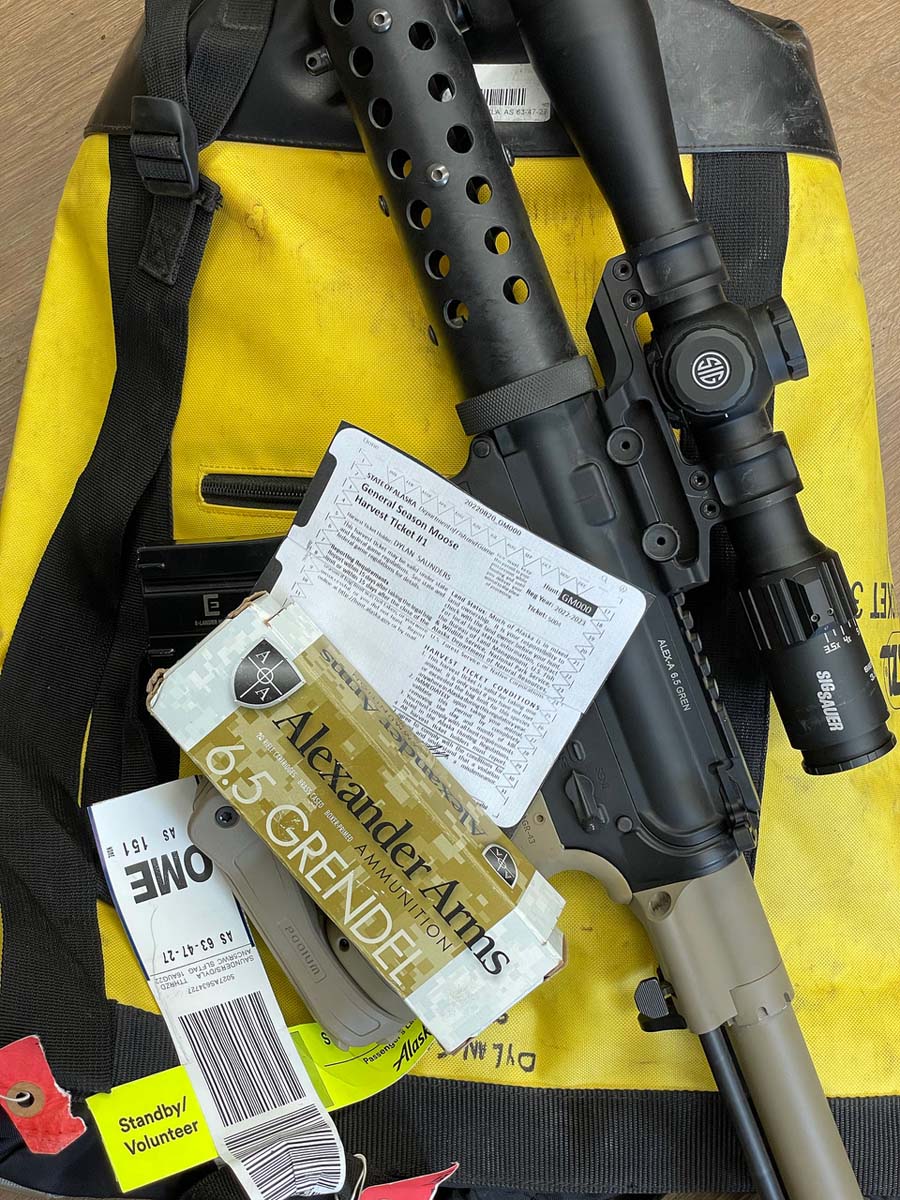

This gun in my hands was an Alexander Arms AR pistol chambered for the 6.5 Grendel, a wickedly effective little cartridge. Its efficiency from a short barrel is legendary. The 6.5 Grendel’s compact size and low recoil belies its brutally devastating killing power. I’ve seen it too many times to doubt it.

The village of Stebbins, Alaska is beautifully situated on the western shore of St. Michael Island on the Bering Sea. The meeting of mountains, tundra, and sea, islands and river systems, and abundance of wildlife results in world-class waterfowl and big game hunting, subsistence hunting, and fishing.

It was in Stebbins that I first became friends with Bernard and Bruce, and with fall approaching, talk turned increasingly to moose hunting.

A trip to the Stebbins Native Corporation office secured a land use permit. The pristine wilderness extending for miles around Stebbins is privately owned and cared for by the local residents through the Stebbins Native Corporation. To hunt on that land, or cross it to state or federal land far beyond without a permit, is to trespass on their land.

The easy part done, I turned my efforts to acquiring a moose tag from Alaska Fish and Game. This proved very difficult.

With an internet service that makes dial-up seem fast, and very poor wireless phone service, it took several days of effort to procure an electronic moose harvest ticket. But in this remote location, I had no ability to print.

A sharp knife and tape, and my harvest ticket was as ready to hunt as I was.

Finally, I got my hands on a broken printer that still had copy capability. After placing my phone on the glass and copying the screen over and over, I dug through a pile of blurry copies to find 2 that could be taped together into a usable harvest ticket.

Access to the Yukon River Delta is only a two hour trip south by skiff on the Bering sea, and a moose hunt on the Yukon is almost a guaranteed success.

But there is an area slightly closer with much more beautiful terrain, and the moose taste better. Having sampled moose from both areas, I opted to hunt north of the Yukon.

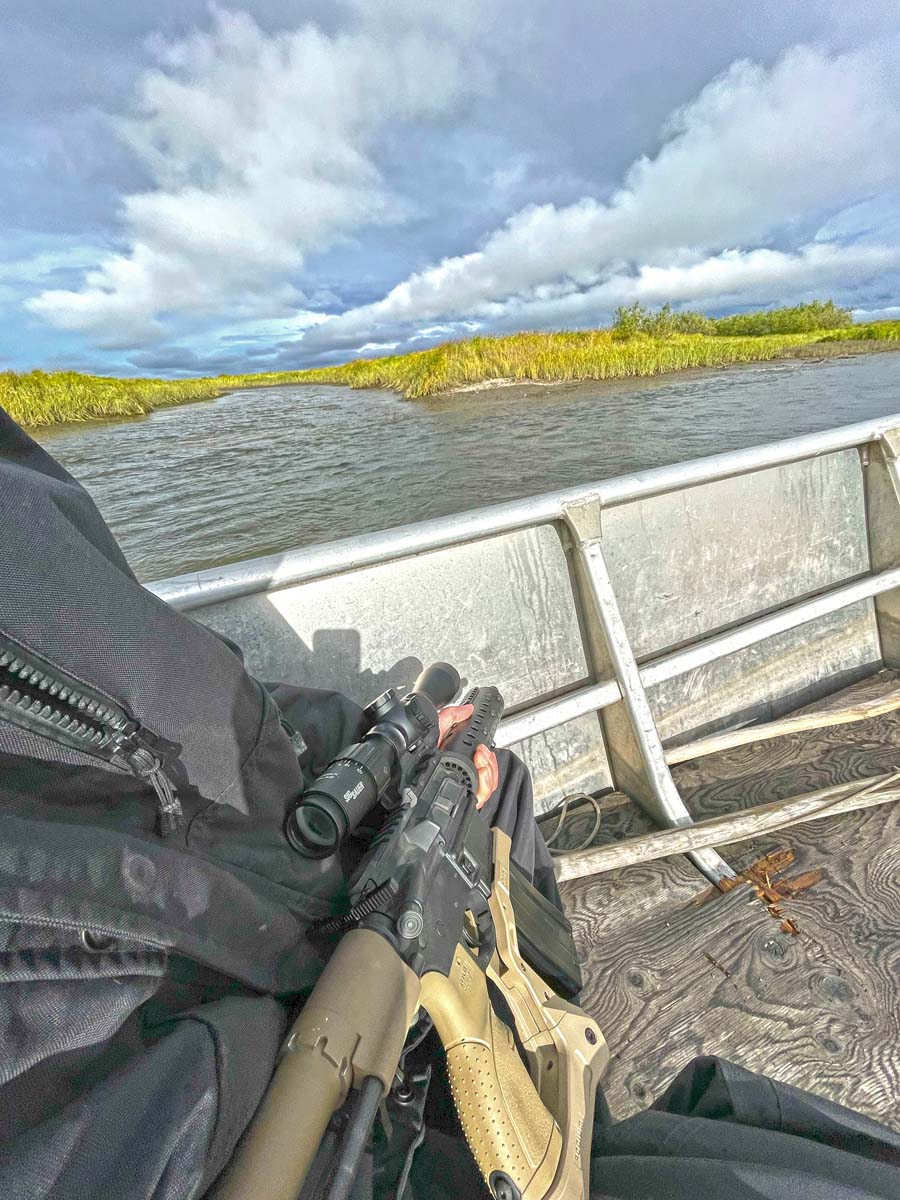

We launched Bernard’s aluminum boat and set out along the Bering Sea coast, then up river and out into the tundra.

As we slipped up through the current, seagulls wheeled overhead and eagles alternately swooped down over the river or inspected us regally perched in the tree tops. Geese, swans, and cranes passed overhead in the hundreds, while ducks skimmed the water as they flew upstream.

The clear river with its clean gravel bed was bordered by willow brush, alders, and poplar before the open tundra stretched away on both sides. The landscape rose gently toward the distant mountains where the river had its origins.

The riverbed and tundra

We saw no moose that first trip, but the wilderness, the scenery, the river, and time spent with good friends made the trip well worth it.

We made several trips down the coast and up the river far enough that it became too shallow to navigate. We walked through the tundra along well traveled moose trails. My 6.5 Grendel was my constant companion, of course, but I also brought along my Alexander Arms .50 Beowulf AR pistol. My Tisas U.S. Army model 1911A1 loaded with Buffalo Bore’s new .45 ACP heavy Outdoorsman ammo was always on my hip in case of an unexpected encounter with an unruly brown bear.

Usually it was sunny. Sometimes it rained. We generally traveled home in the dark after watching spectacular sunsets over the Bering Sea.

The tundra was marked by hooves in all directions. Moose cows and calves watched from banks and beaver ponds as we passed, or crossed the river on gangling legs. Boats regularly returned to town settled low in the water under loads of meat, but I had yet to see a bull.

In what seemed like the blink of an eye, it was the second to last day of the season. One more trip, I decided, and if I didn’t get a bull, I would travel farther south to the Yukon on the final day and shoot a bull there.

We set out in the morning and made the hour-long trip along the coast before heading up river. As we traveled up river, we anchored to the banks and walked out into the tundra to hunt wherever an opening in the brush presented itself.

Heading up the river

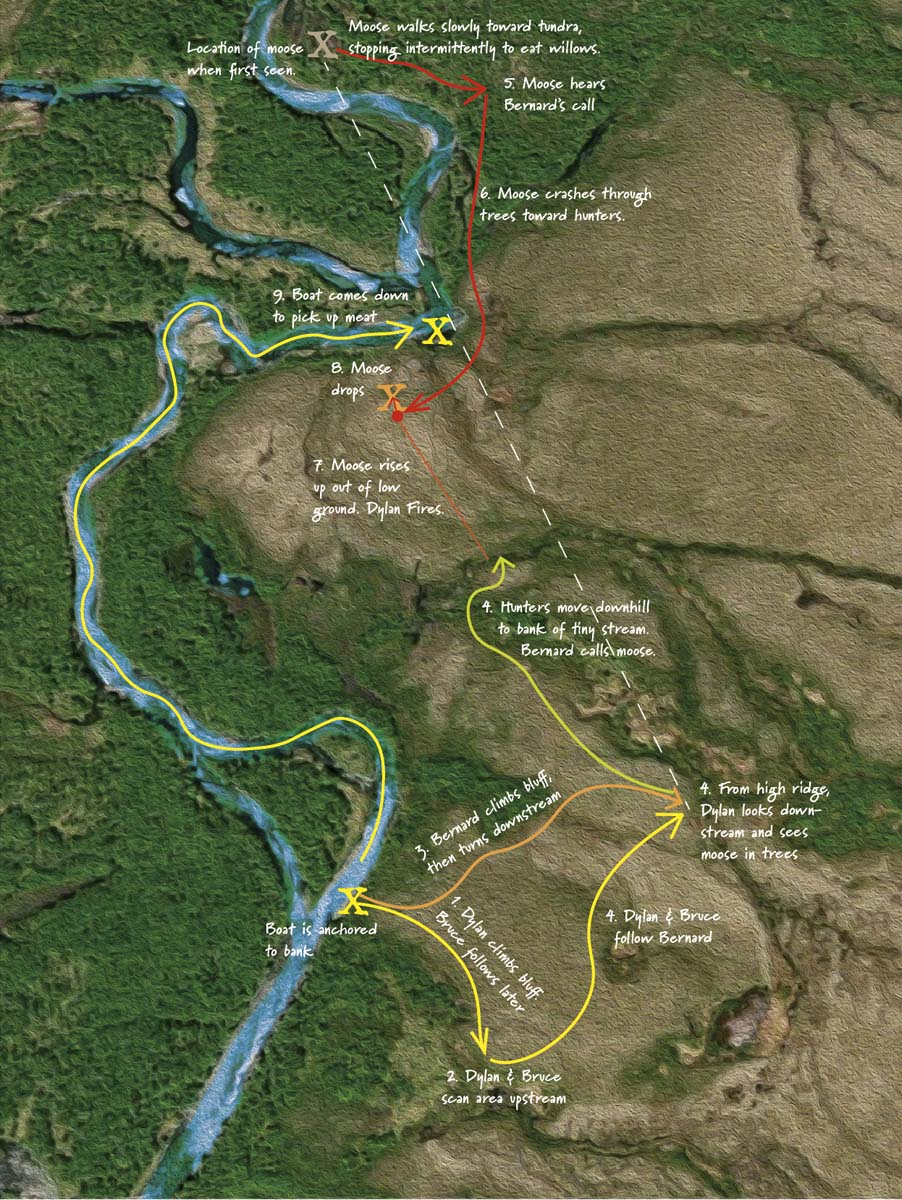

We finally reached the point at which the river became too shallow to navigate in Bernard’s boat before drifting about 100 yards downstream to anchor at the foot of a high bluff, the first place that the land gained elevation beside the river.

After eating some soup made with water dipped from the river, Bruce and I climbed the tundra slope to see what could be observed from the high ground. We walked upstream and watched the area as far as we could see upriver, out into the tundra, and across the river.

After some time we began moving downstream, and saw Bernard climbing toward us. Instead of turning upstream to meet us, he climbed higher and downstream, so we followed. We caught up with Bernard, scanned the area downstream, and stood talking. We were well away from the river now, but a long tundra slope fell away in front of us. The slope flattened out at the toe, stretching away to reach the river where a wide bend cut inland to our front.

Bernard backing me up with the 50 Beowulf

Suddenly, on the far side of the bend, some 1,000 meters distant among trees and thick willows, I saw white paddles moving.

“There he is,” I said quietly as I pointed. The big bull was moving slowly, pausing to clip and chew mouthfuls of willow twigs, on a course that would take him along the far bank of the bend and then out into the tundra perpendicular to us and far out of range.

We began moving downhill. As our elevation dropped, we lost sight of the moose behind intervening trees along the river banks. At the toe of the rise a trickle of a feeder stream had created a wide trench-like depression in the tundra; it’s far bank chest high. We stopped and spread out along this natural rampart, using it for cover.

We could still hear the bull moving slowly across our front, still on a heading to travel out into the tundra and away from us to our right. The position I chose would allow me to see him if he did so, yet still staged me nicely for a shot if he turned toward us around the bend and followed the river.

Bernard cupped his hands to his mouth and called.

Immediately, we heard the bull crashing toward us through the thickest of the trees and willows along the loop of the bend.

Loaded for moose and bear

I chambered a cartridge; the long, sleek Barnes TSX bullet sliding effortlessly into the chamber followed by the gleaming brass of Alexander Arm’s efficient, compact 6.5 Grendel cartridge.

The snapping and crashing of the brush died away and I knew the moose was in the tundra to our front.

Then the tips of his antlers showed over the crest of a slight rise and the moose rose into full view. He moved across the undulating tundra, swaying under the weight of his antlers like a ship rolling in a moderate swell. He strode toward us, scanning the tundra for the bull who had dared to challenge him.

The reticle of the SIG Romeo scope aligned with his chest, steadied, and followed his movement. I waited, reluctant to end the moment. 225 meters. 200 meters. 175 meters.

“Dylan, NOW!” Bernard whispered. His hands rose to his mouth. “UHH!”

The big bull’s attention was arrested and I pressed the trigger.

Under the light recoil of the 6.5 Grendel, the muzzle remained steady and I saw the impact through the scope, hair flying in a small cloud around the point of impact and my reticle remaining centered on the chest.

The moose hunched and began a trotting turn away. My reticle shifted to a point behind the front leg and the trigger broke again. The moose trotted a few more strides, I snapped a quick shot at his neck to try to stop him as near the river as possible, and he halted. He stood where he stopped, facing directly away at 225 meters.

After a few seconds, he haltingly turned toward us, stubbornly keeping to his feet.

I calculated the angle to the spine at the base of his skull, placed the reticle on his right eye, and pressed the trigger. Again, I watched the bullet impact through the scope, which remained almost motionless through the negligible recoil of the cartridge.

Like a tree falling the moose toppled sideways, stiff far legs coming off the ground, slow at first, but gaining speed as the heavy body smashed into the mossy ground, antlers gouging into the tundra, stiff legs rolling up into the air and hanging for a moment. Then the legs rolled back down to the ground and the moose ponderously raised his big head by sheer willpower.

I ascended the lingonberry and Labrador tea-scented bank in front of me and began walking forward.

The moose lay on the tundra, lung tissue covering the ground in a crescent around his left chest. He held his head up for a few moments, and then it dropped to the tundra again, rolled sideways, and his breathing stopped.

Lung tissue destroyed by the 6.5 Grendel bullets paints the tundra.

This was not a time for high-fives and cheering. As taught, I took a moment for silent thanks, my hand on the velvet of the still warm nose.

It was a time for respect and reflection; a pause to consider the small part played in the ancient natural cycle of life, reproduction, and death, sustenance and survival, in which this magnificent animal gave his final gift of life.

It is a cycle that, of all humans, the subsistence hunter knows best, for he is an integral part of the system; a predator, and sometimes prey in a complex ecosystem that he feels in his soul and studies for survival.

It has occurred to me that no photo exists of me smiling in a pose with an animal I have hunted. At the time that cameras come out, I am still in this reflective mindset.

The moment passed and the work began in earnest.

The moose still, knives appeared and the process of butchering began. Killing a moose is the easy part. Everything that follows is pure hard labor.

Bruce’s and Bernard’s sons had walked down the river to us, and now they retraced their steps upstream to guide the skiff down. When it arrived, I put my Grendel in the skiff and took my .50 Beowulf back to the kill in preparation for the possible arrival of a hungry bear.

We gutted the moose and found that the lungs were black, entirely filled with blood. As expected, the first shot had killed the moose. Subsequent shots, intended to anchor the moose near the river proved unnecessary, since the first two shots had so thoroughly incapacitated it.

Butchering the moose revealed the effectiveness of the 6.5 Grendel and Alexander Arms’ ammunition.

The Alexander Arms 120 grain TSX load had launched the solid copper Barnes bullet at 2,265 fps from the 11” barrel. At 175 meters, the first bullet struck the moose at about 1860 fps. Entering the chest, it expanded from .264” to .774” and traveled lengthwise through the body, reaching the far thigh and shattering the femur below the hip joint.

The bull was dead on the first shot; he just didn’t want to admit it.

The second bullet crossed the body to break the far side front leg.

The third shot was a snap shot at a running moose at 225 meters. It missed his spine by just an inch or two and exited the neck.

The final shot found its mark and dropped the moose, which was already dead on its feet.

We rolled the moose onto its left side and skinned it to the ground. It was then rolled to the right side and skinning completed. With the skin creating a clean surface over the tundra, we quickly quartered the moose, and, working in tandem, carried the quarters to the skiff.

Bernard hoisted a full quarter onto his shoulder and back. Bent under the weight, boots sinking deeply into the tundra moss, he walked with shortened gait to deposit the quarter in the skiff.

I attempted to duplicate his feat, but failed under the mass of a hindquarter that weighed more than a whole deer.

Right ribs, then the rear half of the spine quickly followed, and then the left ribs with spine, neck, and brisket still attached proved to be a three-man carry. Handholds were cut in the meat and we hauled it to the skiff.

Now all that was left was the head (in Alaska, the antlers can only be carried out on the last trip, after all usable meat is recovered). Bruce’s son grabbed an antler, I grabbed the other, and we carried it down and placed it in the bow of the skiff.

A loaded Skiff

We pushed off from the bank and slipped downstream. The weight of the meat increased the draft of the skiff, but Bernard’s skill at the helm kept us safely in the often elusive main channel. Younger members of our party made themselves comfortable among meat, hooves, antlers, and velvety nose and drifted off to sleep. Never tiring of this country, I watched the tundra slip by, the eagles standing sentinel over the river from the tops of trees that lined the banks, pocket ducks diving under to reemerge around the next bend.

The light was turning grey when we passed the flocks of hundreds of ducks and geese at the mouth of the river and into the Bering Sea. Bernard lifted his outboard as the skiff ground to a smooth halt.

Unbeknownst to us, weather patterns far south in the Pacific Ocean had caused an unnaturally low tide. The skiff rested firmly on the bottom of the Bering Sea as we settled into the long wait for the turning of the tide.

Bernard stepped out of the boat and walked across the sea floor, the water covering only the bottoms of his boots. It was a strange spectacle to sit off the coast with the sea stretched out around us to the horizons, yet feeling no motion of the sea and watching Bernard appear to walk on the surface of the ocean.

Bernard standing “on” the Bering Sea

The afternoon had progressed into a deep dusk before the bow of the skiff began to lift gently in the wavelets. With the incoming tide and the descending darkness came a light driving rain and wisps of fog, reducing visibility. The skiff finally slid free in the now darkened sea and Bernard felt his way toward deeper water. By now visibility was severely obscured and we were in full darkness. Bruce and Bernard worked together to steer a course farther out to sea to avoid the danger of the now invisible shore.

In darkness, and without navigational aids, this situation could grow dangerous, but I wasn’t greatly concerned. Bernard and Bruce were descended from a long line of seafaring people. Their forefathers routinely performed impossible feats of navigation when traveling this sea though ice, fog, snow, and rain in skin boats so seaworthy that modern technology has provided no improvement on their design. I also knew that Bernard and Bruce were held in high esteem within the community for their skill on the ocean.

A couple hours later my confidence was proven justified, for out of the wet gloom that closed us in, a slightly blacker line in the darkness indicated familiar coastline, followed by the appearance of a glow from the lights of Stebbins as we rounded a point.

The skiff ground softly into the volcanic sand in front of Bernard’s home as excited children spilled from the lighted doorway. Bernard jumped down onto the sand to be immediately inundated with hugs from his younger children.

By now the rain had stopped and the night was cold in our wet clothes. The loader I called for soon arrived and we pulled the skiff up the beach. Bernard’s family had food prepared, and a well appreciated meal of chicken sandwiches and beluga whale re-energized us.

We loaded the meat onto a sheet of plywood placed across the forks of the loader to spend the night safe from marauding village dogs. It would be cut, packed, and distributed the next day.

In this part of the world, hunters hunt, not only for themselves, but for the community. Elders and families who do not have a hunter to provide for them directly still have meat in their homes. These are communities of self-reliant people who truly care for their own.

Stacking meat in the freezer.

Bernard’s son had recently caught a moose, so Bernard declined the offered hindquarter, which he volunteered to deliver to an elder and his family who needed meat. Bruce accepted the brisket and other cuts. Another hindquarter and the tongue were given to another elder, and a couple who had previously shared meat with me from their own moose were invited to come by and take what they wanted. Other community members received meat as well.

The remaining quarter nearly filled an upright freezer, and I ferried some home in coolers on Bering Air and Alaska Airlines. I took the rest out on a chartered PC12 aircraft when winds were too wild for passenger or cargo planes to fly. All that remained was the skull, which was backhauled for me by Desert Air, who were flying in loads of disaster relief materials to us on their DC3.

In all, this moose helped to feed seven families.

Possibly the most appreciative was my two-year-old son. In restaurants on a subsequent trip to the Lower 48, he confidently faced each waitress and placed his order:

“MOOSH meat. Me have MOOSH. MEAT.”