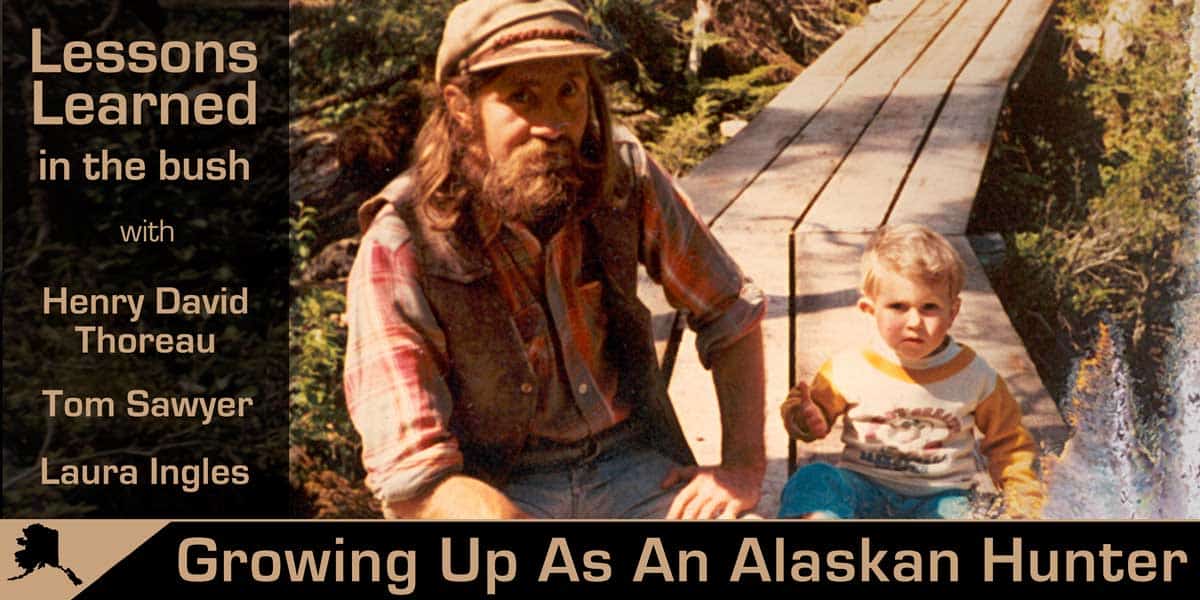

If Henry David Thoreau traveled through time picking up Tom Sawyer and Laura Ingles on the way attend Woodstock together, we’d have a fair representation the village where I grew up. It was the ‘70s and ‘80s as I grew up in a small coastal bush village in Alaska among a handful of commercial fishermen and hard-core holdouts from the 1960s. My childhood was a curious alchemy of lifestyles and values that would not have felt unfamiliar to denizens of the distant or recent history of our nation.

If Henry David Thoreau traveled through time picking up Tom Sawyer and Laura Ingles on the way attend Woodstock together, we’d have a fair representation the village where I grew up. It was the ‘70s and ‘80s as I grew up in a small coastal bush village in Alaska among a handful of commercial fishermen and hard-core holdouts from the 1960s. My childhood was a curious alchemy of lifestyles and values that would not have felt unfamiliar to denizens of the distant or recent history of our nation.

Our town had two buildings that had electricity, a cold storage building where fish were handled prior to being shipped out to processors in other towns, and a school. Both buildings were powered by diesel generators.

We had no roads, and no motorized vehicles other than boats, most of which were wooden and several generations older than their current owners. On school mornings I walked down a single-plank boardwalk to the beach, where I waited with a few other children for a skiff to take us across the bay and deposit us on a dock. The coat hooks in the vestibule of our one-room schoolhouse bristled with the life jackets we wore to school every day.

The closest town with any kind of modern facilities was an hour flight away, or a day by boat. The only way into or out of town was by boat or float plane. A De Haviland Beaver on floats flew in once a week with the mail, and any supplies ordered came from Seattle, with stops in two towns on the way. Those could sit on the dock in the second town for up to a week waiting for the next mail plane to fly.

A couple summers, a produce boat appeared in town, its refrigerated hold brimming with over-ripe fruit and vegetables. Those willing to pay the astounding prices demanded had to immediately eat what they purchased, as we had no refrigeration.

But what we did have was an ocean swarming with fish and other edible aquatic life. We had a rich, temperate rainforest clinging precariously to the sides of mountains; towering spruce, hemlock and cedar, and thick brush that drooped with heavy loads of berries when the season arrived. Living throughout that paradise was game that could be hunted.

My Dad’s Winchester Model 71. He shot more than 50 deer and several bear with this rifle.

What wasn’t native could be grown in gardens behind every house, provided it was of a hardy nature to survive the climate. All were necessary to sustain the life of our village. Survival was tied to seasons and migrations, tides and storms, weather and currents. A hunter-gatherer lifestyle supported the community, and without it, the community would have been forced to drift away, family by family to larger towns. The alternative was financial destitution and literal starvation.

In this environment, I learned about wildlife by observing the relationships between predator and prey, the balance in nature, and about life and death. I leaned self-reliance, reliance on neighbors, and community cooperation. I learned the value of resources, the price of failure. This is the environment in which I was introduced to hunting.

Here are 15 philosophical lessons I learned about hunting while growing up in the Alaskan Bush.

Respect

One of my earliest memories is of a dark, rainy night when I was three years old. The crackling fire in a barrel stove radiated heat through the wood frame house while I played in the warm light of kerosene lamps. The dull roar of the swollen creek and waterfall next to the house imparted a cozy feeling, a feeling increased by the drumming of rain on the tin roof.

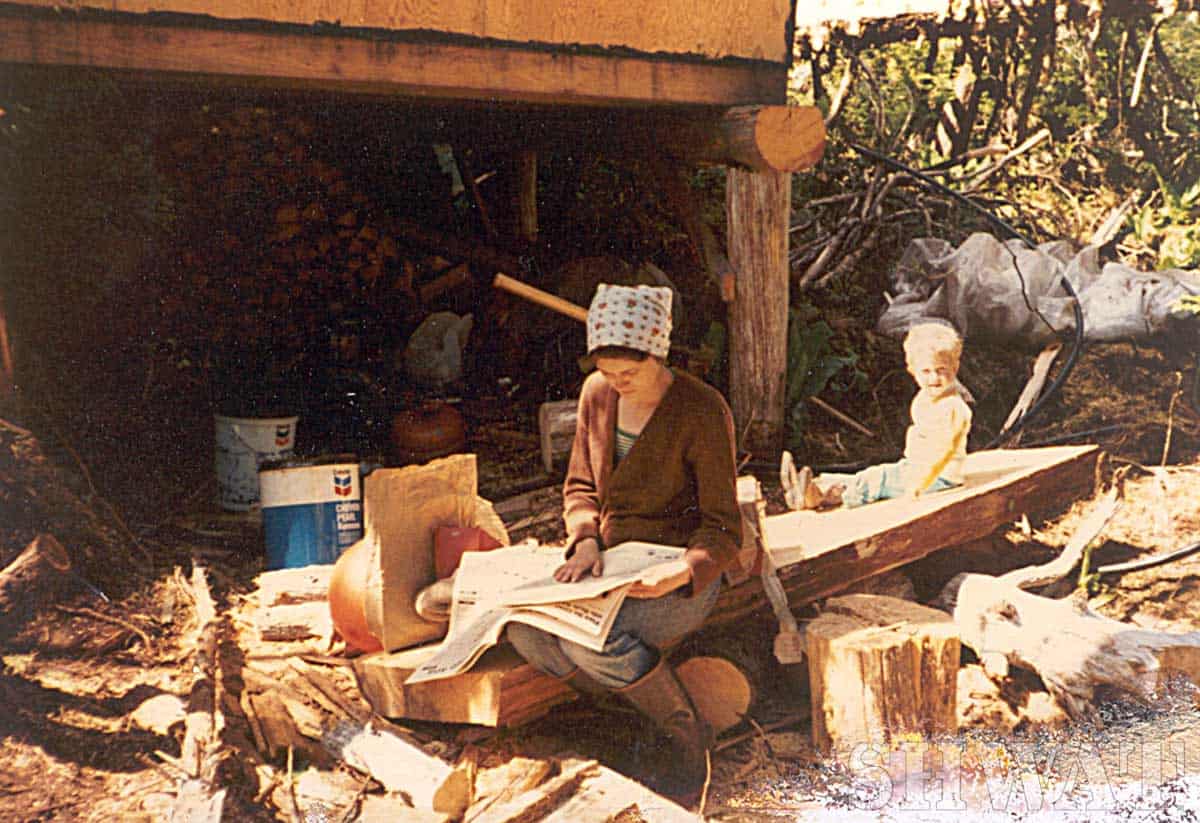

If not for the Chevron cans this picture could almost have been from 1877 instead of 1977.

Another sound intruded; a step on the porch, a turning of the doorknob, and then my father was standing in the open doorway, rain slashing in from the darkness behind him and spattering on the wooden floor. He stood in the doorway, rain gear running with water, as he ejected the fat .348 Winchester Silvertips from his Model 71 Winchester, as I scrambled across the floor to catch them.

Then he leaned the rifle against the wall, stepped out, and stepped back in carrying a blacktail deer, which he hung from a peeled spruce rafter. I stooped down and looked into the open eye of the buck, afraid that it would suddenly return to life, while trying to comprehend death. It would be two more years before I had a fair comprehension of death, but at that age I understood enough to feel sorrow for the death of that deer.

I learned respect for any creature that died so that I could eat. Not starving means killing, whether we kill or others kill, but we can kill in a respectful and humane way. Whether it is a plant, a mollusk, or an animal, we should treat it with respect and refrain from being wasteful.

Since that rainy night in my parent’s homestead, I have never killed an animal that I did not feel some sorrow for, and have only killed when necessary for defense or cleanliness, or when the animal was to be used.

Gratitude

Gratitude

Growing up, getting meat to eat was a painful process. It meat hiking though the most rugged terrain imaginable, then packing an animal down mountains, across creeks and muskegs. Add to that skinning and butchering the animal, then canning the meat. I learned that all food meant sacrifice. A beautiful animal’s life was sacrificed so that I could live. Time and effort were sacrificed to get the meat home, to prepare it, to preserve it.

I grew up in the Alaskan Wilderness Playground, but getting food was no walk in the park.

Today, most Americans insulate themselves from this truth with layers of cellophane. But the fact remains that every time you bite into a burger, you are benefiting from the death of an animal and the work of many hands in raising, processing, and transporting the meat to its final use. Whether we harvest an animal in a hunt, catch it with a hook and line, raise it in a coop or pasture, or buy its meat neatly packed in our local grocery, we should be both respectful to and grateful for the animal that provides us with life.

Self-reliance

The house began to warm again after the intrusion of the night wind and rain. My father had changed out if his wet rain gear and clothing and spread paper under the hanging buck. He quickly began skinning the deer as I watched. Soon he had it skinned down to a level I could reach.

He turned to me and held out a knife. The knife in one hand; pulling on the hide with the other, I laboriously continued the job under his instruction, until the hide was piled on the floor under the skinned animal. I had skinned a deer, participating in the support of our family.

At three years old, not much could have made me prouder. Hunting teaches self-reliance, and self-reliance is a character trait desperately needed in our current society. Self-reliance is not limited to a single pursuit. The man or woman that learns self-reliance through hunting applies it to all areas of life. Instead of saying, “I wish I could do that!” or “I can’t afford to hire someone to do that,” the self-reliant person says, “I could do that, I just need to learn how.”

I have no memory of visiting any bush village where the “I could never do that!” were spoken. It wasn’t until I visited in more urban areas that I began to hear people express disbelief in their abilities to learn or perform certain tasks.

The Remington Model 8 was the first truly successful semi-auto rifle. Chambered in calibers duplicating the popular 1800s lever-action cartridges, it was and still is a popular hunting rifle. It would be decades before militaries really accepted the semi-auto concept, but hunters saw the advantages immediately. The first widely used military semi-auto, the M1 Garand, owes its parentage to the Model 8, and the family resemblance between the Model 8 and the AK-47 is obvious. Kalashnikov may have been a genius, but John Browning was a genius first.

Where I grew up, the hunters themselves did all butchering and meat preservation. I know that there are many areas in which hunters take their game to butchers to be processed and packaged. This is fine if it is what you prefer. But I would encourage any hunter to process and package your meat yourself. It is not hard, you can involve your family, and you will learn more than just to be proficient in cutting meat.

Responsibility

On that rainy night my father stood in the doorway, water running from his rain gear, rifle in hand, and he told why he unloaded his rife before he brought into the house. As I picked up the cartridges, I also picked up important lessons about responsibility and safety. This was the first lesson of many that I was taught simply and practically.

Sometimes the lessons were formal instruction. Sometimes they were taught by example, reinforced with explanation. Sometimes they were instruction or correction given while involved in hunting or other outdoor activities. Sometimes they were stories of the failures or successes of others. Whatever and wherever the individual lessons, hunting taught me responsibility, to take things seriously, even while having fun.

I learned responsibility for my actions or my negligence. Hunting involves the use of tools like firearms, knives, bows, and vehicles. Each item must be used responsibly, with constant awareness and with forethought. I recently saw a video of a hunter who was hunting with other people. He did not take a shot on a moving animal, and later said he did not take it because he momentarily was not sure of his partner’s exact location. That’s acting responsibly.

I once had a beautiful shot on a New Zealand red stag, but my hunting partner was slightly in front of me, off to one side. He told me to take the shot. I have shot right past other soldiers’ heads in the military. I certainly had the skill to take that shot without any danger to my partner. But I did not shoot for two reasons.

First, we were hunting with suppressors, . I knew how loud the sonic crack of that bullet would be and did not want to damage his hearing. Second, and most importantly, I was taught from a very young age not to shoot if someone is down range from me. That is a rule I adhere to when hunting, and that stag was not worth breaking that rule, nor was it worth taking even the smallest chance of injuring someone. My partner took the shot, and I enjoyed the steaks as much as if I had been the one to pull the trigger.

The .50 Beowulf pistol is shorter than the Extra Light Winchester ’86, even with a suppressor attached. The suppressor protects hearing in a bear defense situation and reduces recoil for faster shooting.

I learned that there is no excuse for shooting someone through negligence. “I didn’t know it was loaded,” actually means, “I aimed a loaded firearm at another person and put my finger on the trigger.”

“The gun just fired on its own when I took it off safe to unload it,” means, “I aimed a loaded firearm at another person with my finger on the trigger.”

“It just went off when I was trying to take it our of the boat/airplane/car/case,” means “I aimed a loaded firearm at someone while performing a task known as likely to cause a loaded firearm to fire.”

Responsibility extends to the hunter’s responsibility to the animal he is harvesting. The hunter is responsible to make sure he takes the right animal, to take the animal as humanely as possible, and to handle the animal properly after it is harvested.

This means that if the moose is standing belly deep in a lake, the goat is on the edge of a precipice, the sheep is across an impassible chasm, or anything else that could prevent the recovery of the animal, you don’t take the shot. If an animal does go where it is impossible to recover after you shoot it, you do all you can to accomplish the impossible.

If you think you may not be able to get the meat out before it spoils, you don’t take the shot. If you are unsure about the legality of taking a specific animal in a specific place in a specific way at a specific time, you don’t take the shot.

The rifle that started my love for 6.5mm cartridges, and my most current 6.5.

The 6.5×55 cartridge in the Swedish Model 1896 rifle convinced me of the advantages of 6.5 cartridges long before theGrendel and Creedmore brought US popularity to the 6.5s. Modern powders and cartridge design have decreased barrel lengths, but not performance.

Both the 6.5 Grendel and its Swedish great-grandfather are fully capable of taking any North American game up to black bear, and I might shoot a brown near with either if conditions were right.

Once you do have an animal on the ground, you are responsible to that animal, and to other families who might depend on hunting for their meat, to immediately care for it. You are responsible to pack out all of the usable meat, and pack it out in a usable condition.

Once the animal is on the ground it is yours; you own it, you are responsible for it. You don’t waste it, because there are other people who would have used it if it had been left for them to harvest.

You don’t leave one animal to rot because you saw a larger trophy on your way out. You don’t leave it to rot because the mountains are tall, the brush thick, and the pack out too difficult.

When you chose to take a life, you are responsible for that life. If you take a life due to negligence, you are responsible for your negligence and should face consequences for your actions. If you take the life of an animal in hunting, you are responsible for the treatment and use of that animal. To kill an animal and fail to use it appropriately equals wanton killing for the sake of killing and exposes a deep character flaw. The exception to this, of course, is when animals must be killed for the sake of self-defense, preservation of livestock or livelihood, or to cull invasive species in the conservation of native environments.

More Lessons

As you can see, this was a unique growing up that laid the groundwork for my future, That future would include life as a company level sniper in Iraq and various roles in the Shooting, Hunting and Outdoors industries. Stay tuned for Part 2.

Well said and well reasoned! Thanks for writing this Dylan

Good article. Very nice blend of good values and intrigue. I have a very similar background, being raised in the Alaskan bush. I think these lessons apply universally, and applaud your ability to articulate them punctuated with personal experiences. It’s probably no coincidence we also share tastes in firearms. My first rifle purchase was a 6.5 Mauser that I found to be an excellent weapon form many years, but has been practically supplanted by a Grendel carbine. I did have a 50 Beowulf for a time but one has not yet replaced my M71 .475 Turnbull.

It would be hard for anything to replace a .475 Turnbull M71!

I loved reading this. Brought back memories of my own childhood on a farm in VA. Not nearly remote as Dylan’s experience but the same lessons were taught in my home. Valuable and sorely missing from today’s family environment.