You have sights on your rifle, and you may not even know how to use them.

Aperture sights (receiver, peep, ghost ring, tang, bullseye, whatever name you know them by) have been in use since the 1400s when some unknown marksman or armorer drilled a hole in a piece of wood or metal and attached it to a crossbow for a rear sight.

An aperture sight can be a receiver sight, tang sight, mounted on the barrel, or mounted on the bolt. Whatever the style, it has a hole (an aperture) through which you look at the front sight.

Anyone who has shot modern military-style rifles with iron sights has probably used aperture sights. However, most are doing it wrong.

Some years ago in a shooting class, I noticed all of our students were using optics. I picked up a rifle and shot the class alongside the students using iron sights. Most of the students were astounded that I could shoot accurately and as fast or faster than them using iron sights. They did not think it possible. We learned that many of the students across many courses had never fired a rifle with iron sights.

I’ve been an iron sight shooter all my life. I grew up with a father who confidently took shots with iron sights that most hunters wouldn’t attempt with a scope. I never owned a scope until I began using scoped rifles in the military.

From my father I learned that the first thing to do with any new iron-sighted rifle was to install a rear aperture sight.

You should be skilled with iron sights. They don’t require batteries, most don’t have delicate parts or adjustments, and they aren’t made of glass. They are rugged and reliable.

But even those skilled with notch and blade style (partridge, buckhorn, etc.) sights usually don’t understand an aperture sight.

Why Aperture Sights are the Kings of Iron Sights

Here is what you need to know:

Aperture sights are faster.

You can get on target faster with an aperture sight. Their use is simpler and more intuitive than other types of iron sights. The reason will become clear as you read on.

Aperture sights are more accurate.

Before modern scopes became widely used for long-range competition, sniping, and hunting, aperture sights remained the standard for precision shooting. Today, precision shooters using iron sights still peer through these apertures.

Aperture sights don’t require a conscious alignment of front and rear sights.

This is the secret. If you are attempting to align the front and rear sights, you are doing it wrong. You will actually be slower and less accurate.

Aperture sights usually work better than other types of iron sights for people who have issues with vision or struggle with focus due to age.

How to use aperture sights:

Look THROUGH the rear sight.

Focus ON the front sight.

Place the front sight on the intended point of impact.

Squeeze the trigger.

That’s all there is to it. Look through the rear sight and then ignore it. Your eye will automatically align the front sight in the center with far more accuracy than you could consciously.

In addition to speed, ease of use, and accuracy, aperture sights have some other advantages:

When used correctly, aperture sights manage parallax.

If you keep the front post out of the fuzzy area of the rear ring and the aperture’s diameter becomes completely contained within the diameter of the pupil of the eye, an aperture sight can reduce or eliminate parallax.

Aperture sights bring your target into better focus.

When you focus on a close object, far objects are out of focus. Therefore, when you focus on the front sight, your target is out of focus. An aperture can bring your target into better focus. Smaller apertures increase this effect. The longer your sight radius, the more the aperture can bring your target into focus.

In the same way a pinhole camera can, apertures can create slight magnification of the target

This is all you need to know to understand the correct use of aperture sights. Again, look through the rear iron sight and ignore it. Focus on the front sight and align it with your target. That’s all.

Now you know how to use your aperture sights. If you want to explore some different styles of aperture sights, and the science behind what makes aperture sights work, read on.

Styles of Aperture (peep) Iron Sights.

Important: The outstanding performance of aperture sights is centered in the round aperture. Several companies offer sights in other shapes, I.E. clover-leaf or diamond. These shapes result from misuse and misunderstanding of aperture sights. Either the manufacturers themselves misunderstand the science behind aperture sights, out they are marketing to the public’s misunderstanding. These styles of sights are designed to be deliberately aligned, with the angular shapes or points providing alignment reference. This almost completely negates the advantages of an aperture sight and this type of sight tends to be slower and less accurate.

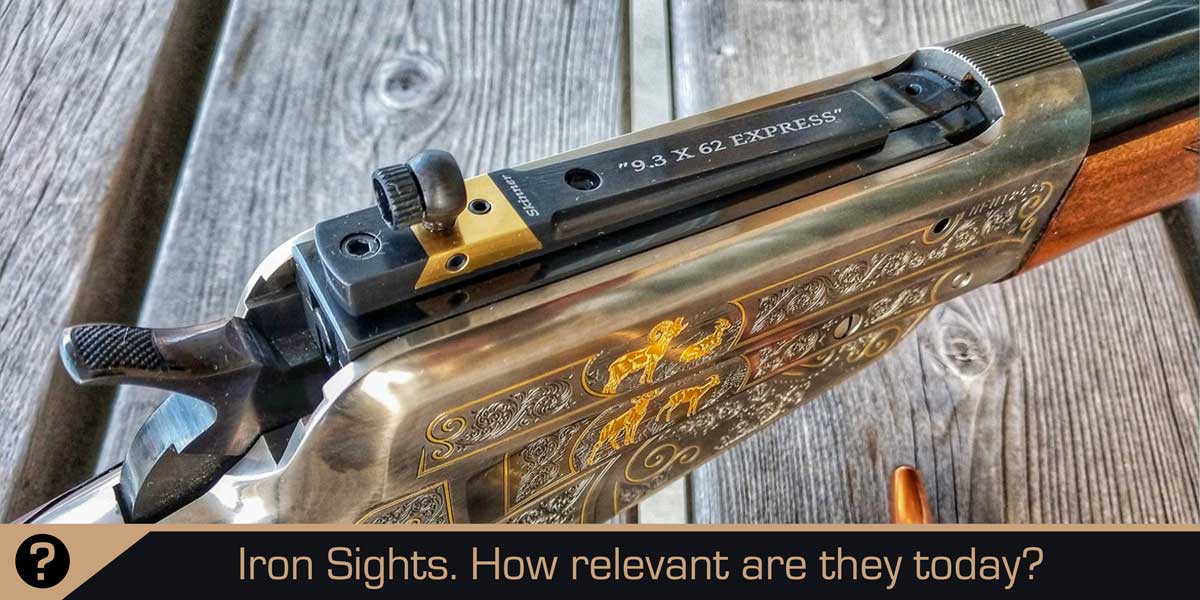

Tang Sights

Tang sights were among the first modern aperture sights. They mount to the top tang on traditional style rifles, like single-shots and lever actions. In the 1800s, buffalo hunters and competitors routinely hit targets at 1,000 yards or more using black-powder cartridges like .50-120, .45-90, 45-70, etc. using tang-mounted aperture sights. Mounted behind the receiver on long-barreled rifles, they offered a very long sight radius. They often paired with an aperture front sight. Marble Arms makes a good option if tang sights are your preference. The disadvantage is that they are somewhat delicate, and are close enough to sometimes hit your eye on a rifle with heavy recoil.

Receiver-mounted Aperture Sights

These sights mount to the receiver itself. One early example is the Lyman Model 21. First designed for the 1895 Winchester, whose long bolt knocked over tang sights like bowling pins, it mounted to the side of the receiver. This style sight evolved into a variety of aperture sights that mounted to the sides of lever-action, bolt-action, or single-shot receivers.

Providence Tool Company offers a reproduction, and Lyman and Williams offer side receiver-mounted aperture sights for almost any modern or historic rifle.

During the same era, Marlin began offering their Hepburn sight that mounted to the top of their Lever-action receivers. Today, Skinner Sights builds a more robust, modernized Hepburn-style sight for Marlin and Henry lever-actions.

Skinner also builds receiver top mount aperture iron sights for several types of bolt action and semi-auto rifles.

Modern military rifles and modern civilian-market semi-autos tend to have receiver-mounted aperture sights, either built-in or removable as the primary sighting system, or folding as a backup to an optical sighting system. On AR-15 rifles, I have used a number of fixed and folding sight systems. On some ARs, I have replaced the apertures with Meprolight tritium apertures. This helps contrive a hit in full darkness, while not being bright or noticeable in the light to distract from the circular aperture. I use FAB Defense backup sights on a lot of my rifles because they are robust, intuitive, and affordable.

Bolt-mounted Aperture Sights

Sometimes aperture sights can mount right to the bolts. A number of fine custom Mausers have sights mounted on the cocking piece, often as a backup to a scope. I have a Winchester Model 71 with an outstanding aperture sight mounted on the bolt. The sight itself is worth almost as much as the rifle, and is quite rare.

For anyone desiring a modern bolt-mounted peep sight for a lever-action, Skinner carries excellent options. Steve’s Gunz carries a great sight option for Rossi lever-actions that both replaces the problematic safety and offers a better sighting system.

McLaughlin offers a Rigby Style bolt peep sight for Mausers and similar bolt-action rifles.

Barrel Mounted Aperture Sights

The receiver or the tang are usually the best places to mount an aperture sight to benefit from all of the advantages aperture sights offer. However, there are often good reasons to avoid an aperture sight mounted to the receiver. Drilling holes in the receiver of a historic rifle is a sure way to drop hundreds of dollars off of its value.

In these cases, a peep sight mounted in place of the original sight makes more sense. While the sight radius isn’t as long, and the aperture has to be larger, the increased distance from the eye makes it look smaller and it still works well, retaining most of the advantages of an aperture sight.

Skinner Sights manufactures aperture sights that mount to existing barrel dovetails in rifles that have them.

Mojo Sights manufactures both front and rear aperture sights, designed to mount in place of the original sights on classic military rifles without permanent alteration.

Focusing on the Science

Here is a quick look at why and how aperture sights work. We will only scratch the surface here. You can gain a more complete understanding with a little research.

Have you ever strained to see something more clearly? Perhaps you were not wearing glasses. Perhaps you have perfect vision, but the object was distant, or the ambient light very bright. What did you do?

Chances are, you squinted. When you squint to bring something into focus, you are using your eyelids to create a sort of aperture. I have seen people who, without their corrective lenses, make a circle with their fingers and look through it to read distant text on a sign or menu. This is also an aperture.

Now a photographer or optometrist should have a good understanding of what we are dealing with here. When light is transmitted through a lens and strikes a receptive service, whether the surface is a film, a CCD or CMOS, or the retina of an eye, the focal length between the lens and this surface needs to be correct for the object to be in focus.

So imagine a screen and a projector. You project an image on the screen, focused to the exact distance from the screen to the projector. The image is sharp. But if you focus the image at a distance somewhere between the projector and the screen, the image will still be on the screen, but it will be blurry.

This is how our eyes work, but unlike a projector projecting a single image, your lens projects images from different distances simultaneously. What is focused on our retinas is determined by our eyes at the distance that light reflects from objects. If you focus on an object three feet from your face, and on an object 300 feet from your face, one of the two will be out of focus – it will be projected through your lens at the wrong focal length and will not be focused in your retina.

So when you focus on your front sight, your target will be slightly out of focus, and your rear sight will be slightly out of focus. If you use a partridge-style rear sight (notch) you will be trying to align your front sight, your blurry rear sight, your blurry target, and your eye.

But an aperture actually focuses light, in much the same way a pinhole camera works (if you have never built one, you should). So light coming through an aperture is bright as it closely focuses in your eye, similar to having a corrective lens in front of your eye. The smaller the aperture, the more pronounced this affect. The front sight is still in focus, but the aperture changes the depth of field; it adjusts the point at which the image gets focused by the lens in your eye. It brings it closer to the retina and the target looks less blurry. For this to work, the aperture must be smaller than the aperture of the eye itself, of course.

The aperture also reduces the amount of light passing through to the eye. Bright ambient light or light reflecting from other objects, especially nearer objects, in the surrounding environment can interfere with they eyes ability to focus on and decode the light reflected from the target. An aperture reduces the amount of light transmitted to the eye and increases clarity of the target.

Alignment of Iron Sights

For simplicity, we often say that the eye automatically aligns the front sight in the center of the aperture. That is true in a sort of practical, simplistic way, but is not technically the whole story. The human eye does tend to automatically center an object focused on in the center of an aperture that is being looked through, but this is less important than most people think.

What is extremely important in parallax suppression.

If the aperture’s diameter is smaller than the eye’s pupil diameter, the aperture becomes the entrance pupil for the entire optical system of the eye and sight picture. This includes target, front sight, rear aperture, and the eye. When this happens, parallax suppression is achieved.

What does this mean? It means that it does not really matter exactly where the front sight post is visually within the aperture. It does not matter if it is exactly centered or not. Accuracy is not affected. The lower the ambient light, the better the parallax suppression.

This sounds crazy and counterintuitive, but it works.

If you practice focusing on the front sight and ignoring the rear, you will understand what most shooters don’t; how intuitive, fast, and accurate iron sights can be.